Sauvignon blanc can be a pretty strident, demanding grape at times. But while some people like their wine to shout loud, I prefer a bit of restraint and subtlety.

Sauvignon blanc can be a pretty strident, demanding grape at times. But while some people like their wine to shout loud, I prefer a bit of restraint and subtlety.

For this reason, I tend to favour sauvignon blancs from France over those from the New World. This is, of course, a sweeping generalisation, and there are some lovely, subtle examples of wines made from this grape in parts of New Zealand, South Africa and Chile. But, as a rule of thumb, France tends to be my first port of call.

A few weeks ago a couple of my colleagues, Richard Bampfield and Chris Kissack, joined forces to put on a tasting of some fairly unusual sauvignon blancs (and some rather more conventional sauvignon blanc blends). I say unusual because all of the wines in the tasting had been aged in oak and then aged further in bottle. While this is quite typical treatment for sauvignon blanc blends from Bordeaux, it’s rarer to find pure sauvignon blanc that has been aged in oak, and rarer still to find that these wines have been aged for longer than a year or two once in bottle. (For the most part, sauvignon blanc is prized for its bright aromatics, and these are at the height of their intensity while the wine is young.)

With a few exceptions (foremost among them Château Brown and Château Smith-Haut-Lafitte). The overall impression was of wines that took themselves too seriously. On the whole they were overly alcoholic (a couple of them were over 15% above – a figure rarely seen in even the ripest New World whites these days) and over-oaked.

By comparison, the single-variety examples from the Loire were masterpieces of restraint and elegance (actually, many of them would have been masterpieces of restraint and elegance even without the comparison).

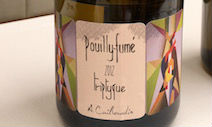

I was particularly impressed by Cailbourdin’s Triptyique, a 2012 from Pouilly-Fumé. Aged for 12 months in large-format barrels (300- and 600-litre sizes) the wine showed little evidence of any of the spice characters associated with oak use. What it did get from the oak, though, was the broadness of palate associated with gentle micro-oxygenation (minute gaps in the oak allow for gentle oxygen exchange) and a certain amount of polish. This rich mid-palate texture worked harmony with vibrant acidity to balance the wine’s rich fruit (mandarin peel, lemon and fresh-cut grass, along with hints of smoky minerality).

An example of the same wine from the 2008 vintage suggested that the 2012 has a long future ahead of it. The aged version had settled into refined middle age, retaining much of its bright aromas and crisp acidity, with an enhanced degree of that smoky minerality. Still plenty of vigour, as demonstrated by the long, layered finish.

I’m not all that sure that I would pair this wine with anything too complicated, food-wise. Let it shine with a piece of simply cooked white fish – or, at a pinch, its depth of fruit might allow it to cope well with the punchy flavours of halibut served with a salsa verde.

Rating: ![]() . (What does this mean? See here for a guide to my rating system.)

. (What does this mean? See here for a guide to my rating system.)